Not long ago, NPQ published an article by Jon Pratt that discussed how nonprofit workers, particularly in the human services field, often remain undercompensated. For a long time, nonprofits went along with local governments, underpaying for the human services nonprofits provided. In my home city of New York, nonprofits have mobilized in recent years to press the case for full funding of their contracts with local government. Increasingly, their efforts have elevated awareness of the need to fairly compensate an essential and committed nonprofit workforce. In New York City, this highly educated workforce is primarily women of color. Momentum is building to rectify glaring pay disparities.

New York City has long contracted with nonprofits to provide social services. Over 80,000 workers in the nonprofit human services sector provide essential assistance related to homelessness, foster care, family services, mental health, elder care, youth, persons with AIDS, workforce training and placement, and other services. This year, the city has nearly 4,600 contracts with human services organizations that are together providing $5.6 billion in services.

Seventy-five percent of this workforce are workers of color and seven out of 10 are women. Women of color thus constitute 55 percent of the nonprofit human services workforce, nearly twice the 29 percent representation of women of color in the city’s overall private sector. However, chronic underfunding of city contracts means that this well-educated workforce is woefully underpaid. As documented in a recent report by the Center for New York City Affairs, where I direct economic policy work, median pay and benefits for human service workers are 20-35 percent less than for similarly-educated workers in comparable positions in city government and elsewhere in the private sector. Overall, in the city’s nonprofit human services sector, two-thirds of full-time workers had 2019 earnings at or near the city’s poverty threshold.

Who are these workers? They include social workers, counselors, and their supervisors. They work in a range of areas, including child welfare, mental health, substance abuse prevention and treatment, and elder care. While over half of nonprofit human service workers have college degrees and a quarter have graduate-level degrees, the average 2019 pay of nonprofit workers was $34,000, about the same as that of restaurant or laundry workers, $14,000 a year less than clothing store workers, and less than half of what hotel workers earned. Benefits are similarly limited. Unsurprisingly, even before the pandemic, the city’s nonprofits had trouble recruiting and retaining professional workers.

A History of Low Wages

Settlement houses and various religious and secular charitable organizations have a long history, in New York City and elsewhere, of providing a range of human services to low-income communities. The provision of government-funded human services grew sharply during the 1960s, when federal Great Society programs were launched. At the local level, services continued to grow in response to the AIDS epidemic, the early 1990s crack epidemic, an aging population, and the de-institutionalization of those with mental health issues. Federal welfare reform in 1996 pushed many mothers of young children into the paid workforce, increasing the need for childcare subsidies and afterschool programs. As housing affordability pressures intensified over the past 15 years, New York City substantially increased its contracting for homeless shelters and services.

For over half a century, publicly funded human services provision has been channeled through nonprofits rather than city agencies. This fostered community-oriented approaches to service delivery, but it also was done to keep city costs down. Unlike city employees, there is relatively limited unionization among New York City nonprofits. Low union density in the sector has meant low levels of advocacy to improve conditions for workers at city hall and in Albany. As a result, nonprofit wages have remained depressed.

Meanwhile, the nonprofit human services workforce grew rapidly, doubling in the past 30 years—at a rate more than two-and-a-half times faster than that of private sector employment. Employment in home health care services, where worker pay has been rock-bottom, has grown even more rapidly. (Under the recently-enacted New York State budget, home care wages will rise by $3 an hour.)

Rather than fund services based on the actual cost of providing high-quality services and fairly compensating a well-educated workforce, contracts are set at the lowest price possible. This system has forced nonprofits to operate at extremely slim margins and reduces the possibility of human service workers earning wages and benefits that are on par with comparable positions in the public or private sectors. Nonprofits that heavily rely on government contracts to pay their staff and provide services have felt they have little choice but to accept underfunded contracts.

Over the years, city contracts (and state contracts for some programs in foster care, domestic violence, and a few other areas like home health care) have left many New York nonprofit service providers in a precarious financial position. Following the bankruptcy and dissolution of one of the largest citywide multi-service nonprofits—the $250 million a year Federal Employment and Guidance Service (FEGS) organization—a task force established by the Human Services Council reported that government contracts covered, on average, only 80 percent of each dollar of “true program delivery costs.” City contracts, for example, typically provided very limited funding for indirect costs that include administration, information technology, and rent. Several years of advocacy on the part of nonprofits were needed to get the city to finally commit in 2019 to increasing the allowance for indirect costs.

Nonprofit-Public Sector Pay Disparities

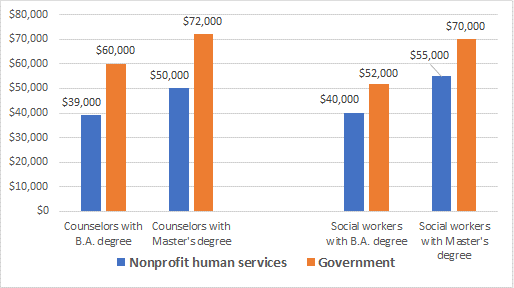

The chronic underfunding of nonprofits has resulted in wages for human services workers that do not reflect broader labor market conditions and that create enormous pay disparities. The chart below demonstrates these disparities.

Nonprofit versus Public Sector Wages, New York City

These pay disparities range from 21-23 percent for social workers and 31-35 percent for counselors. Workers of color are heavily affected. There is an even greater gap when it comes to health care, retirement, and other employment benefits. For city employees, benefits average about 50 percent of wages; for nonprofit sector workers, benefits average only 36 percent of wages. With this benefit gap factored in, total compensation for nonprofit sector counselors with a master’s degree is 37 percent less than for similar public sector workers.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In recent years there has been some belated recognition on the part of government that the human services nonprofit-government pay gap is untenable and must be narrowed if not closed. Increasingly, nonprofit organizations and their workers are mobilizing to pressure city and state governments to increase compensation levels.

Essential Workers?

It’s a familiar story, but it’s worth observing that nonprofit human service workers have been on the frontlines throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Nonprofits adapted quickly, locating personal protective equipment so they could provide in-person services like shelter operations and food allocations, and they shifted online to provide services like telehealth and job support. Workers of color were over-represented in frontline roles during the pandemic, furthering their risk of exposure.

A survey conducted for a June 2021 report from a sector task force convened by the Human Services Council (HSC), the sector’s umbrella organization, found that 82 percent of nonprofits launched new services and 72 percent expanded services in response to the pandemic. Despite this, the city reimbursed nonprofits for an average of only 38 percent of pandemic-related expenses, underscoring many organizations’ financial precarity. The report, Essential or Expendable?, emphasized the urgent need for the city to address the glaring nonprofit-government pay disparity.

Under the tag line, #JustPay, HSC organized a massive city hall rally on March 10 of this year to press the case for the FY 2023 city budget to include greater funding for nonprofit wages. The rally featured supportive speeches from the city comptroller, the leader of the powerful AFSCME District Council 37 union, and several city council members. Eloquent testimonials at the rally reflected the commitment of frontline human services professionals and the personal financial hardships they endure. These testimonials were captured in short videos available on YouTube.

What New York Can Do

To address the glaring pay and benefit disparities between nonprofit human services workers and similar workers employed by the city, New York City should adopt a prevailing wage approach and establish a wage-and-benefit schedule for all contracted human services workers, putting city and nonprofit employees on an equal footing. These compensation benchmarks should then be incorporated into all contracts, along with the funding to support career advancement and promotion opportunities.

Recognizing that this entails considerable resources—as much as $1 billion or 1.5 percent of city tax collections—the city might phase in funding. A first step could be to provide a significant cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) increase. This won’t close the compensation gap but would be a valuable sign of good intentions, particularly given the high level of inflation over the past year.

Is pay equity feasible? Recent experience with early childhood education (ECE) center teachers shows that achieving parity is possible.

The conditions of early childhood center teachers became a front-burner issue in 2014 when New York City began to implement full-day universal pre-kindergarten, relying heavily on nonprofit ECE centers to do so. At that time, pay for teachers in the nonprofit sector lagged far behind pay for public school kindergarten teachers covered by the United Federation of Teachers contract. Following years of organizing, rallies, and temporary fixes, the city committed in July 2019 to phase in starting-pay-salary parity for certified teachers in nonprofit centers, raising the teachers’ pay by close to $20,000, or 30-40 percent. Many of the center-based teachers belonged to AFSCME, and the union’s District Council 37 was instrumental in forging the agreement, which covered nonprofit teachers. While further steps are needed to achieve full parity, the ECE salary parity commitment was a historic breakthrough, with significant implications for the human services workforce and for pay practices in the ECE sector around the country.

Designing City-Nonprofit Contracts with Wage Justice in Mind

While New York City, with its roughly $100 billion budget and its enormous population of 8.8 million people, is hardly your typical US city, the gap between public sector and nonprofit wages in human services is not unique to the Big Apple. City-funded human services typically support low-income households, people with special service needs, and specific vulnerable populations. The need for these essential services is well-established and widely appreciated. There should also be public support for fairly compensating the nonprofit workers providing those services. But far too often, that workforce is neglected.

This must change. In New York City—“ground zero” of the first wave of COVID-19 in the United States—these frontline workers demonstrated their tremendous commitment to helping New Yorkers in need by feeding and caring for thousands during the pandemic’s worst days. Of course, this commitment to the public has been a hallmark of nonprofit human services everywhere. Yet nonprofit workers routinely earn less. Indeed, I encourage readers outside of New York to examine the wage gap in your own communities.

The fact that this wage disparity is so common does not justify it. City governments—both in New York City and beyond—must treat highly skilled, human service nonprofit workforces—largely consisting of women of color—as well as they treat their own employees. The time for pay equity is now.